By Christy Albright and Clarissa Sorensen-Unruh

This part is where we integrate belonging, not belonging, and belonging uncertainty with grief. We’re going to look at grief through very specific lenses – hope, efficacy, resiliency, and optimism – according to positive psychology, and specifically, psychological capital.

First – A Quick Etymology Lesson

Grief is a response to loss and a universal human experience, much like belonging. Grief is sometimes called bereavement or mourning. Bereavement originates from bereafian, an Old English word that also gave us the words rob and deprive, and mourn, which originates from morna, which also gave us the word remember. Grief derives from the Latin gravis. “The Latin adjective [gravis] meant ‘heavy, weighty,’ and it formed the basis of the verb gravare ‘weigh upon, oppress.’” (Ayto, 1990, []s mine). We believe a feeling of being robbed or deprived, remembering, and feeling the gravity, heavy weight, or oppression of the situation are all part of the grieving process.

So, to sum up…

Granger Westberg, in his book Good Grief: A companion to every loss, posits that there are little griefs that we experience daily and big griefs, like the death of a loved one. Little griefs might include change, like a major change at work or in a relationship, etc. A little grief can also refer to when an expectation goes unfulfilled.

OK – let’s have a brutally honest moment. Both of us hate the application of size to grief. What does the size even refer to? The depth of grief one feels about it? The length of time one grieves that thing? Should I feel guilty about grieving less about the death of my dad than the death of my dog? That said, there is something strangely comforting in knowing that our disappointment can result in just as intense a grief as the death of a family member. Talking about grief size, helps us talk about grief in terms of a broader scope of instances, and that helps us recognize grief more regularly than we might have previously.

Stages of Grief

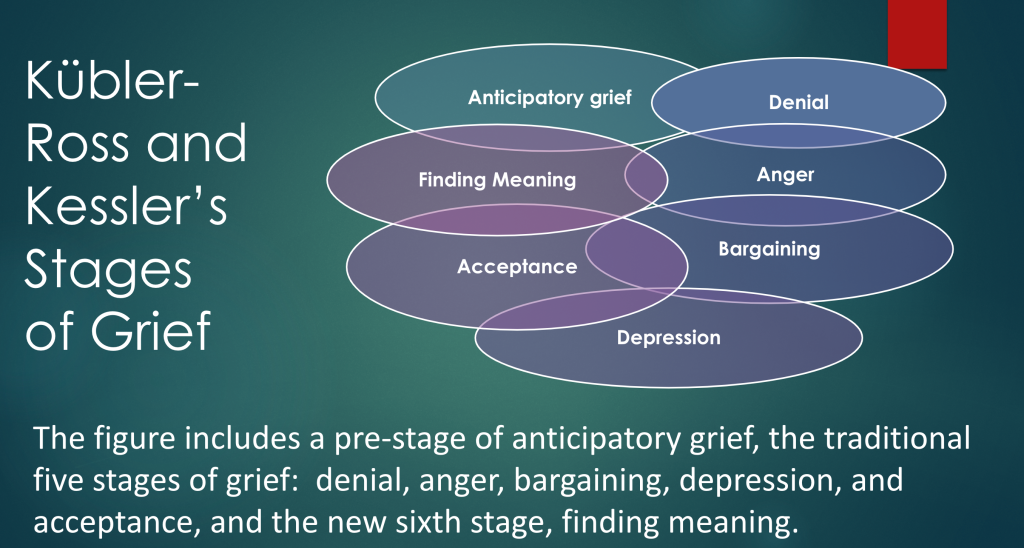

The figure shows overlapping ovals in colors ranging from aqua to purple, and each oval has a stage of grief: anticipatory grief (pre-stage), denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance, and finding meaning (a new sixth stage).

Although Kubler Ross and Kessler use the word stages, neither meant that these experiences within grieving occur linearly. Instead, they suggest that most people experience these when they grieve. Both of us can attest to experiencing the same stage more than once and skipping some stages depending on the grieving experience.

Grief and Psychological Capital

Psychological capital, often shortened to PsyCap, was introduced by Fred Luthans in an effort to enhance positive organizational behavior. “PsyCap is concerned with ‘who you are’ now and, . . . ‘who you are capable of becoming’ in the future.” (Luthans et al., 2015, p. 6) Hope, efficacy, resiliency, and optimism were determined to be “psychological capacities that can be measured, developed, and managed for performance improvement” (Peterson et al., 2008, p. 342). They became the cornerstone of PsyCap and the resources that filled the reservoir of PsyCap.

Of course, if PsyCap can be beneficial for individuals in the workplace, it can be used by individuals outside the workplace. Christy posited in her dissertation that PsyCap can be a tool to help us navigate grief.

Grief and HERO

Hope, efficacy, resiliency, and optimism, sometimes referred to as HERO, interplay with one another. Like instruments in a quartet, an instrument that doesn’t play is not suddenly considered absent from the quartet. It is performing a vital part in the arrangement by resting (i.e. keeping silent). So it is with HERO – one of the four might seem silent in a given moment of life, but that does not mean it is not present.

In PsyCap, hope is both willpower: An individual’s determination to achieve the goals they create or adopt for themselves (Avey, Luthans, Jensen, 2009, p 680) and waypower: “being able to devise alternative pathways and contingency plans to achieve a goal in the face of obstacles” (Avey, Luthans, Jensen, 2009, p. 680). A quick, but powerful, definition of hope is the ability to see a future you want to move toward.

In grief, we can strengthen our hope by looking for ways to move forward that you are willing to put time and effort into (determination, grit) [willpower] and by looking for possible ways forward, steps that look do-able (within your capabilities) and steps that look just beyond your capabilities (baby steps, self talk, looking at past successes) [waypower].

Efficacy is the belief that you can do it. When you have efficacy, you understand your strengths and use them to keep moving forward amid life’s circumstances. Efficacy is a belief in self that encourages movement.

In grief, we can strengthen our efficacy by being specific about what is going well, celebrating our strengths and practicing using them to reach our goals, specifically naming a strength when giving a compliment or celebrating our own accomplishments, and being gentle to yourself, especially in your self-talk. (Self-Efficacy, Communiqué Handout, 2010)

Resiliency is the “capacity to rebound, to ‘bounce back’ . . . ” (Luthans, 2002a, p. 702) It’s “being strong against challenges and being able to pull oneself together” (Gautam & Pradhan, 2018, p. 26). Resiliency is the desire to get up and keep going.

In grief, we can strengthen our resiliency when we make realistic plans and take steps to carry them out; encourage a positive view of ourselves and confidence in our strengths and abilities; practice skills in communication and problem-solving; and manage strong feelings and impulses (Luthans, Avolio, & Avey, 2007, p. 7).

“PsyCap optimism differs from traditional optimism, however, in that it has the caveats of being both realistic and flexible” (Culbertson, et al., 2010, p. 423). It is an underlying knowledge that things will be ok.

In grief, we can strengthen our optimism by celebrating successes, acknowledging what specifically made it a success, remembering those successes when there is failure, always looking for ways to improve, refusing to use negative labels when talking about others or in your thoughts about yourself, taking on challenges and remembering fear and anxiousness are normal when doing something new. (Scott, 2015 and Larson, 2009)

Grief and Belonging

Where does grief end and belonging begin? Unfortunately, belonging brings its own kind of grief. Why? Because to belong to something means that some will not belong or will feel uncertain that they belong. Every group we belong to draws the circle around US, and therefore excludes THEM (Cormier, 2015).

There is also grief in trying to draw the circle big enough to include everyone as much as possible, yet knowing some will choose not to belong or don’t feel included in spite of our efforts.

And then there is sometimes grief that bubbles up even when we do belong, but belonging is not enough to enable us to feel like we can be as open or accepted as we’d like to be. Some may argue that this state is not, in fact, belonging. Yet we have experienced this in groups we had long belonged to when there is a shift in the power dynamics or the balance of the group and we suddenly feel psychologically unsafe in the group. It takes time to make the personal boundaries needed to say goodbye in this kind of situation. And the process is always grief-filled.

So, grief and belonging are inextricably intertwined. But what if we started to visualize belonging grief (the grief that we feel when we belong, or don’t belong, or have belonging uncertainty) through the lenses of PsyCap? Since grief is universal human experience that each human experiences with nuance for the human and the experience, here are four questions to consider when we integrate the lenses into belonging grief:

- What would hope look like in the midst of belonging grief?

- What would efficacy look like in the midst of belonging grief?

- What would resiliency look like in the midst of belonging grief?

- What would optimism look like in the midst of belonging grief?

How would this reorientation and reframing through the lenses of PsyCap change our perceptions of belonging as well? How does it change how we feel when we try to help others belong and fail? Or how we perceive space that we might belong but, for whatever reason, don’t?

Clearly, the PsyCap reframing adds to the nuances of how grief and belonging exist in collaboration with one another. But it also offers gentle guidance for how belonging and grief might be framed regularly and how we might cope with belonging grief specifically in the communities we build.

References

Avey, J. B., Luthans, F., and Jensen, S. M. (2009). Psychological capital: A positive resource for combating employee stress and turnover. Human Resource Management, 48(5), 667-693. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20294

Ayto, J. (1990). Dictionary of word origins: The histories of more than 8000 English-language words. Arcade Publishing.

Cormier, D. (2015, August 27). Community learning – every ‘we’ makes a ‘them’. Dave’s Educational Blog. https://davecormier.com/edblog/2015/08/27/community-learning-every-we-makes-a-them/

Culbertson, S. S., Fullagar, C. J. and Mills, M. J. (2010). Feeling good and doing great: The relationship between psychological capital and well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(4), 421-433. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020720

Gautam, P, and Pradhan, M. (2018). Psychological capital as moderator of stress and achievement. Indian Journal of Positive Psychology, 9(1), 22-28. https://doi.org/10.15614/ijpp.v9i01.11737

Kessler, D. (2019). Finding meaning: The sixth stage of grief. Scribner.

Kübler-Ross E. and Kessler, D. (2005). On grief and grieving: Finding the meaning of grief through the five stages of loss. Scribner.

Larson, Katherine (2009). Teach your kids to operate with optimism, raise inspired kids. Retrieved from http://raiseinspiredkids.com/files/rik_publica-ons/operatewithop-mism.pdf

Luthans, F. (2002). The need for and meaning of positive organizational behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(6), 695-706. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.165

Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J. and Avey, J. B. (2007). Psychological Capital Questionnaire. Mind Garten. http://www.mindgarden.com

Luthans, F., Youssef-Morgan, C. M., and Avolio, B. J. (2015). Psychological capital and beyond. Oxford University Press.

Peterson, S. J., Balthazard, P. A., Waldman, D. A., and Thatcher, R. W. (2008). Are the brains of optimistic, hopeful, confident, and resilient leaders different? Organizational Dynamic, 37(4), 342-353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2008.07.007

Scott, Elizabeth (2015). How to instill optimism in your child. Retrieved from http://stress.about.com/od/parentingskills/ht/raiseoptmists.htm

Self-Efficacy: Helping children believe they can succeed (2010). Communiqué Handout: Volume 39(3). Retrieved from https://www.forsyth.k12.ga.us/cms/lib3/ga01000373/centricity/domain/31/self-efficacy_helping_children_believe_they_can_suceed.pdf

Westberg, G. E. (2019). Good grief: A companion of every loss. Fortress Press.

2 thoughts on “Belonging Part 3: Belonging, Not Belonging, and Grief”