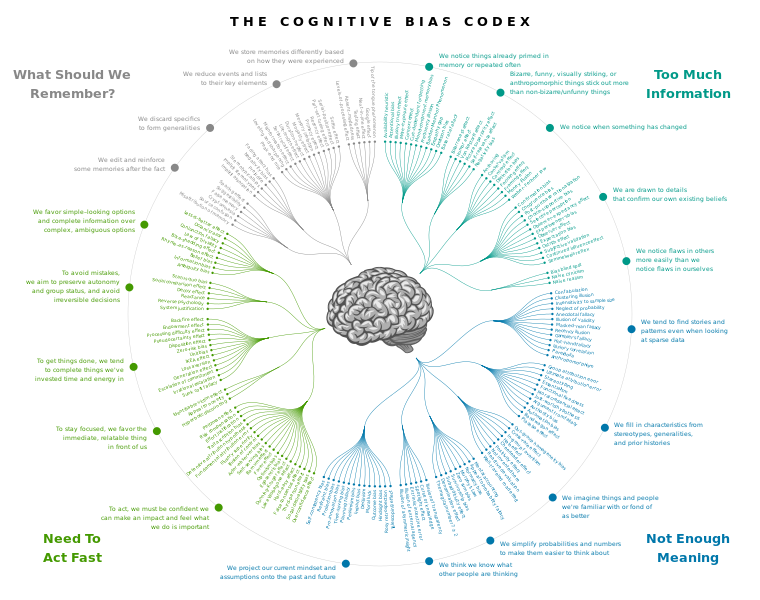

This part of the blog series discusses cognitive biases – one of my favorite topics to discuss. And the topic of my favorite infographic on the web, which is here. A preview (this is the .png not the infographic) is here:

What are cognitive biases?

Ok, before I endlessly wax rhapsodic about *how much* I love this infographic, let’s discuss what cognitive biases are. Cognitive biases are autonomic schemas and heuristics – shortcuts – that grow from systems associated with how humans process and interpret information. We develop cognitive biases over our lifetimes as we encounter and learn from our life experiences. Once developed, these shortcuts enable us to make decisions quickly with little effort and attention. (Wording in italics is remixed from the NSF Game Changers Academy Learning Module on Cognitive Bias, written by D. Kardia and K. Mack)

Our cognitive bias shortcuts are not always accurate, however. They require slowing down and thinking carefully (i.e. slow thinking) to acknowledge and work around so that we can tackle more complex, wicked problems.

[NOTE: Folks often confuse the idea of cognitive biases with the word bias, which Oxford Languages/Google defines as “prejudice in favor of or against one thing, person, or group compared with another, usually in a way considered to be unfair.” Cognitive biases aren’t the same thing as biases, y’all. Cognitive biases are how our brains cope with the overwhelming number of inputs living in our world requires.]

A Sampling of important cognitive biases that often undermine belonging

What are some of my favorite cognitive biases that specifically undermine belonging? I’m so glad you asked…

Most of my favorite simple depictions of cognitive biases are found at this website (also immediately below), which organizes 50 of the most recognizable cognitive biases we use in modern life by the overarching theme – memory, social, learning, belief, money, politics – the cognitive bias exists to help us deal with.

This infographic is fun to play around within…just like the cognitive bias codex is. But it hasn’t answered the question of which cognitive biases undermine belonging most effectively.

Fundamental (or Ultimate) Attribution Error

The Fundamental Attribution Error – the idea that we judge what we see as a faulty behavior and blame it on a person’s character (or some other fundamental aspect of who they are) rather than on their circumstances or on their situation (while doing the opposite for ourselves) – is perhaps the most dehumanizing of the cognitive biases. Charles Schultz captured this cognitive bias repeatedly in Peanuts, and this strip shows why:

The Fundamental Attribution Error is SO easy to fall into and SO hard to spot in ourselves. But if it dehumanizes fellow humans best, it also undermines belonging best because it gives no room for situational issues for our fellow humans, but ALL the room in the world for situational issues for ourselves.

An example: If our students are late, they must be lazy. Or stupid. Or both. But if I’m late, it was a bad morning.

In the immortal words of Charlie Brown – “good grief.”

More information on the Fundamental Attribution Error can be found here.

Stereotypes

Stereotyping takes the fundamental attribution error, which is for individuals, and amplifies it for groups. And then, to make things even worse, stereotyping adds historical prejudice and VOILA! You’ve now made assumptions about behaviors for entire groups of humans that are demeaning and dehumanizing.

Argh.

Geoff Cohen talks about stereotyping in terms of belonging like this:

In my research, I have grappled with the social fact of stereotypes, with their power to blind us to the distinctive, surprising, complicated individuality of those we encounter. Stereotypes lead us as ordinary people in our everyday lives to threaten the belonging of others, even when we don’t consciously believe the stereotypes.

(Cohen, 2022, p. 108)

Pygmalion Effect

Ah, the Pygmalion Effect (or the self-fulfilling prophecy cognitive bias).

The image below really sums the Pygmalion Effect up nicely. Our actions towards other impact other’s beliefs about us. Their beliefs in turn effect their actions toward us, which of course reinforce our beliefs about ourselves.

Talk about a vicious cycle, which can go in both positive or negative directions.

How does the Pygmalion Effect lead to belonging? Or a lack of belonging?

Beliefs and expectations can profoundly effect belonging. Within the education research, Rosenthal and Jacobson (1968) found that “when teachers believe in their students, they teach more…All in all, teachers who ‘expect more, get more’ …which leads them to craft a classroom situation that inspires students and helps them perform better” (Cohen, 2022, p. 94 citing work by Rosenthal & Jacobson, 1968).

So, here’s my interpretation (which I’m pretty sure I read a version of this in Rosenthal and Jacobson so this may, in fact, be paraphrasing): when members of a group believe or expect someone outside of the group to belong to the group, if that person joins the group, they will perceive that they belong more intensely than someone whom the groups believes does not belong.

Oi.

Overconfidence Effect

The overconfidence effect – you think you can predict people’s behaviors way better than you actually can. Even if they are close friends.

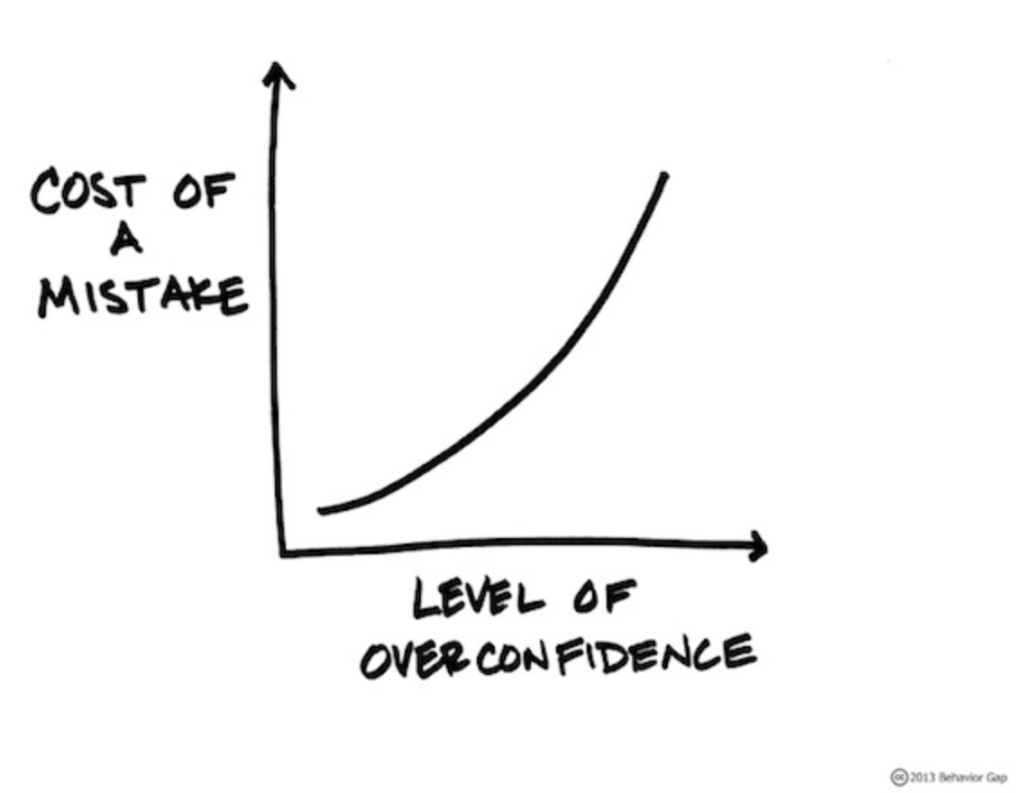

The overconfidence effect talks about others’ behaviors, but can also be discussed in terms of expertise and mistakes, as in the graphic above. This image is a positive exponential graph of “Level of Overconfidence” vs. “Cost of Mistake”. So the greater your level of overconfidence, the exponentially more your mistake will cost.

Cost who, I might ask? But apparently that’s less important.

From a belonging standpoint, the overconfidence effect has profound implications. We think we know how people will behave. But we really don’t.

Geoff Cohen says this about the overconfidence effect and its effect on belonging:

When researchers ask people to predict others’ behavior, even the behavior of people they know well, they are far less accurate than they think they will be…In general, we overestimate how much of a team or an organization’s performance, and even the quality of our own relationships, depends on picking the right people rather than creating the right conditions for them to thrive.

(Cohen, 2022, p. 100)

Bonus Extra Cognitive Biases

I thought I’d add a few extra cognitive biases that we should consider in general, but definitely in terms of belonging.

Consensus Bias (False Consensus Effect): We think people agree with us more completely and often than they actually do. This cognitive bias is particularly problematic in power differentials when one party is silent.

Belief Bias: The tendency to judge arguments based on the plausibility of the conclusion rather than the strength of the evidence.

Dunning-Kruger/Lake Wobegone Effect: The less we know, the more confident we are. The more we know, the less confident we are.

There it is, folks. So many cognitive biases to choose from, so little time. And ALL of these undermine belonging in their own special ways.

Can We remove or eliminate Cognitive Biases?

All of this leads us to the question – Can we remove or eliminate cognitive biases?

And the answer here, unless we are able to invest a lot of time, effort, therapy, etc., is basically NO.

They are automatic y’all. But here’s what we can do:

- We can realize that we have cognitive biases and recognize when we’ve been biased in a specific situation (especially when something seems off or doesn’t feel true). We can also practice recognizing our biases regularly.

- We can reflect on those cognitive biases and decide whether they reflect our core values and beliefs.

- We can rewrite the story our brain has developed using those cognitive biases.

Let me know your thoughts, comments, questions, etc. in the comment section below, if you feel like doing so. Otherwise, thanks for reading!

References

Cohen, G. L. (2022). Belonging: The science of creating connection and bridging divides. W.W. Norton & Company. https://wwnorton.com/books/9781324065944

Rosenthal, R., Jacobson, L. (1968). Pygmalion in the classroom. Urban Rev, 3, pp. 16–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02322211

One thought on “Belonging Part 1.5: Cognitive Biases (The hidden threats to belonging)”